GUEST BLOGGER KERRY ARADHYA

It’s easy to look at an invention—from one as simple as a paperclip to one as complex as a self-driving car—and forget about all the hard work that went into creating it. It’s also easy to overlook the fact that playing with existing ideas or knowledge likely “played” an important role in the creative process.

The value of playing

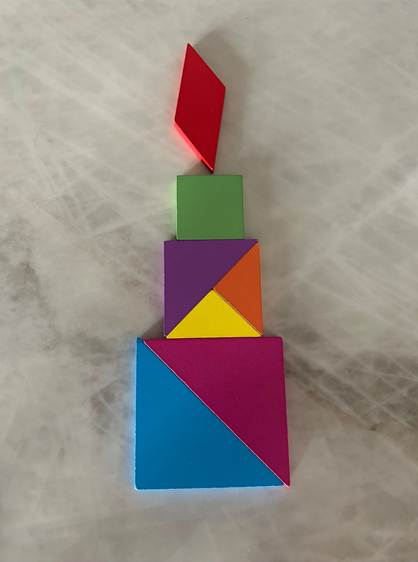

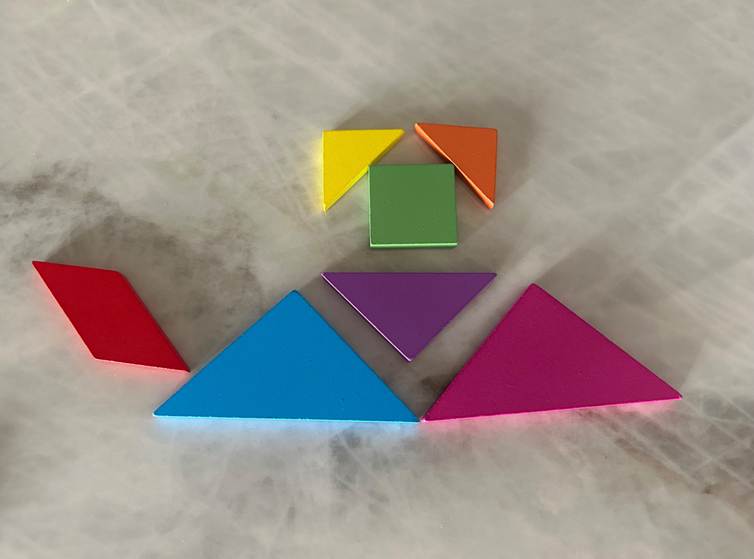

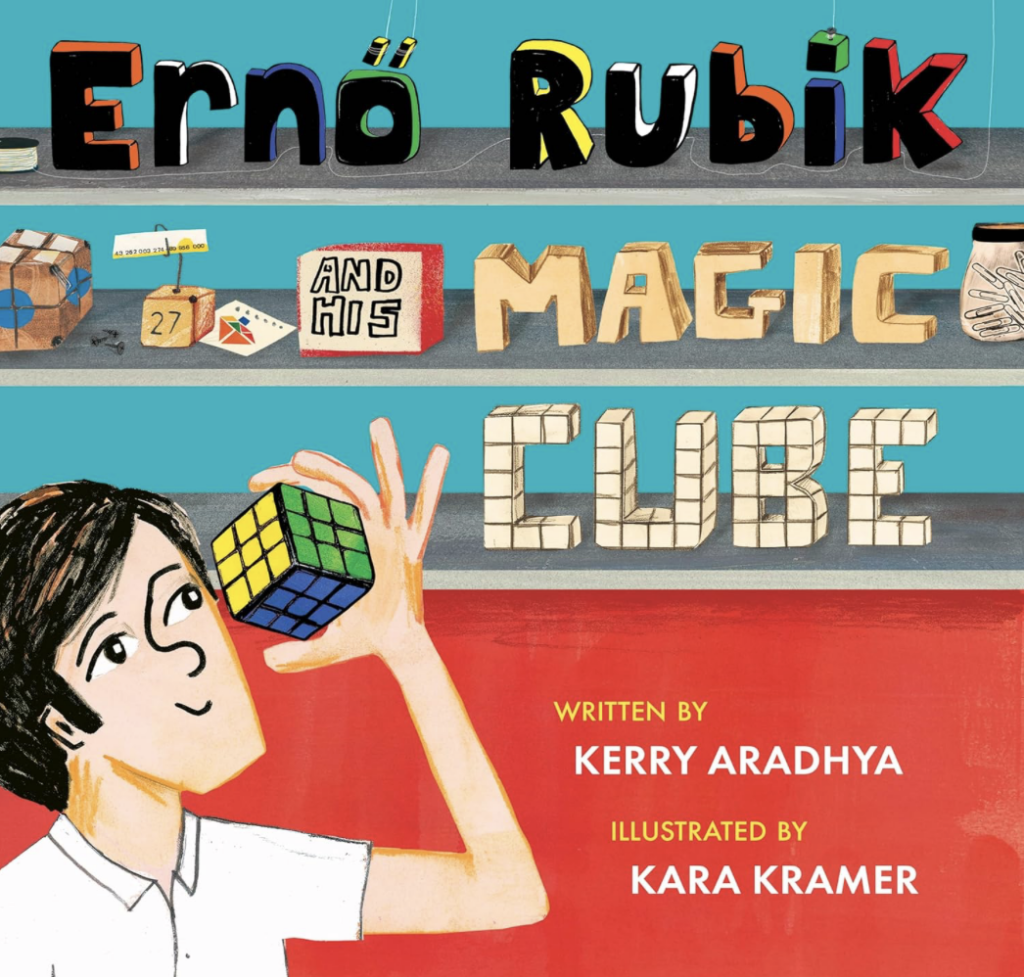

As a young boy growing up in Budapest, Ernő Rubik loved playing with geometric puzzles like tangrams, pentominoes, and pentacubes. He familiarized himself with the shapes in these puzzles, experimenting with different ways to fit them together. Many years later, his creation of the Rubik’s Cube prototype was in some ways an extension of his childhood play. Twenty-nine-year-old Ernő Rubik was simply playing with geometric shapes once again, this time seeing if he could create a cube out of smaller cubes that twisted and turned around each other without falling apart. He had no idea he would end up creating what would one day become a worldwide phenomenon!

Preparation

Talk with your students about tangrams, pentominoes, and pentacubes. Discuss how they are made up of shapes that the students are already familiar with, but that they can be used to invent new and interesting shapes. Then read Ernő Rubik and His Magic Cube. Ask the students to observe the tangram puzzles in the story and look for other unique ways that illustrator Kara Kramer incorporated geometric shapes into the book.

Activity 1

Give each student a copy of this activity sheet, available on page 7 of this online puzzle pack. Have students cut out the seven pieces of the tangram puzzle. Alternatively, students can use wooden or plastic tangram puzzles if they are available in your classroom or at your school.

Ask the students to use their tangrams to copy, or recreate, the four images at the bottom of the activity sheet: the letter E, a spin top, a bird, and a cat.

Activity 2

Have the students clear their desks of any images from the book. Then think of an object (for example, a cat, a hot air balloon, a house, or a candle). Ask the students to create it, in any way they would like, by playing with their seven tangram pieces. Feel free to go through this exercise with a second or third object if time allows.

Discussion

Compare and contrast the two activities, engaging your students in a discussion about the creative process.

- Was activity 1 (copying images from the book) or activity 2 (using your existing knowledge to create new objects) easier?

- Did activity 1 help prepare you for activity 2? If so, how?

- Was one activity more fun for you than the other? What made it more fun?

- In activity 2, did all of the objects the class created look the same? Or did people come up with different designs for the same object? In what ways did they differ?

- Did anything about either activity surprise you? (When I tried activity 2, I set out to make a cat, but what I made looked more like a dog! I also had more fun than I thought I would playing with the puzzle pieces and seeing what ideas I could come up with. It really energized me!)

- What did you learn about yourself by playing with your tangram?

- What did you learn about the creative process?

Encourage your students to take the tangram activity sheet home and continue playing with their tangram pieces. Who knows what new and surprising ideas might arise!

Featured image credit: “Rubik” by Toni Blay is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Kerry Aradhya is children’s author, freelance scientific editor, and dancer who loves puzzling over words and immersing herself in the creative process. Her debut picture book, Ernő Rubik and His Magic Cube, has won numerous accolades including a Mathical Book Prize Honor and an Ezra Jack Keats Honor for illustrator Kara Kramer. Kerry lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband, their two daughters, and one cute but naughty pooch named Sofie. Visit her online at kerryaradhya.com or on Instagram @kerry.aradhya.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.