GUEST BLOGGER JESSICA FRIES-GAITHER

Asking and answering questions is at the heart of every scientific practice, whether in a classroom or in a research laboratory. Doing so is also a key literacy skill. Yet despite its importance, students often struggle to think of questions.

One strategy to help students become more curious thinkers is to help them develop their observation skills. This ability does not develop on its own. Students need practice looking closely and attending to details that might be overlooked with a cursory glance.

As students become more adept at noticing, they will naturally think of more questions. This instructional sequence can be used in either science or English Language Arts class to spark student observations and generate questions.

Set the stage

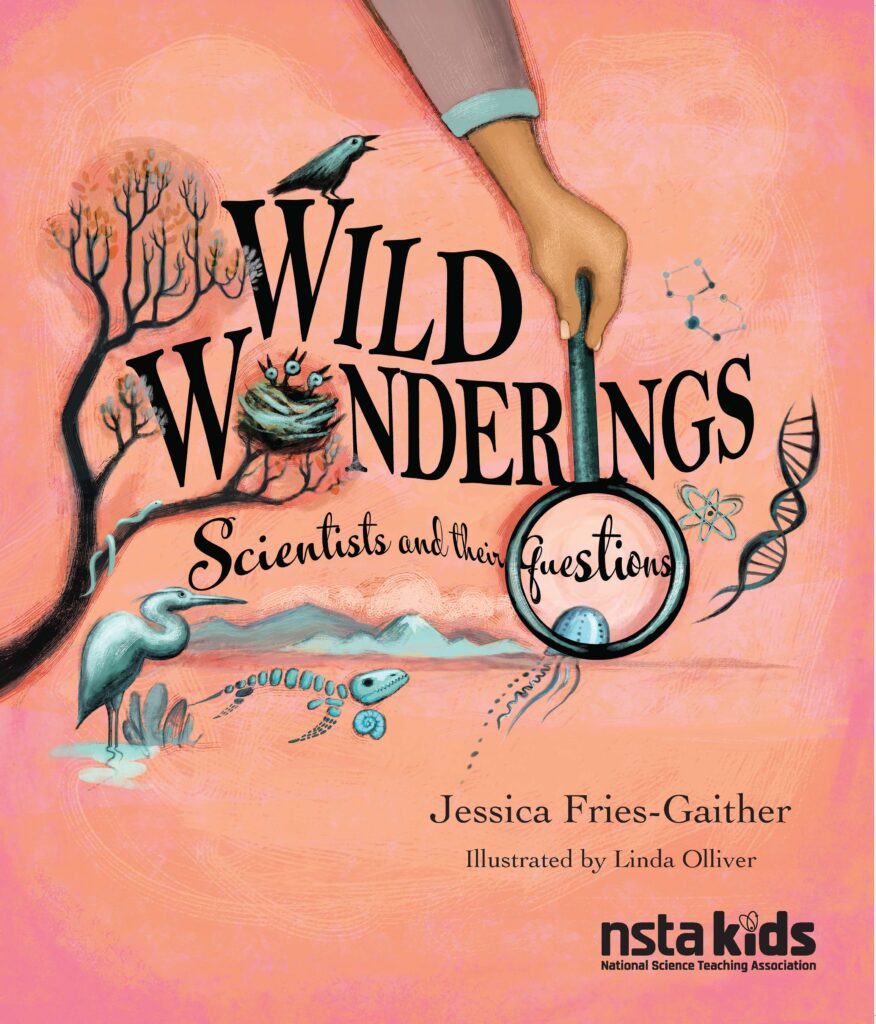

Begin by reading aloud Wild Wonderings: Scientists and Their Questions. Ask students to listen for the different questions posed by the featured scientists and highlight how, in many of the examples, an observation by the scientist led to the formulation of their question. Explain to students that just like the scientists in the book, they are going to practice making observations and then asking questions related to what they notice.

Provide an interesting object

Curiosity begin with an object that warrants sustained attention. Capitalize on the high-interest nature of science by providing natural specimens such as rocks, shells, preserved insects, or plant material for students to examine. If possible, collect enough specimens for each student to choose his or her own object. If that is not an option, you can still conduct this lesson with a single specimen for the entire class to work with.

Promote close looking

In order to make good observations (and ask good questions), students need to slow down and look closely. Provide magnification tools such as hand lenses and/or jeweler’s loupes and encourage students to really notice tiny details. Invite them to take the perspective of an ant and imagine crawling all over their object, paying attention to what they notice as they travel.

Record observations

Ask students to record their observations in writing. You can support students by providing sentence starters like I notice… or I see/hear/feel/smell to target specific senses. (Note that it would be a rare occasion where students would use their sense of taste to observe!) Encourage students to write down as many observations as possible for use in the next step.

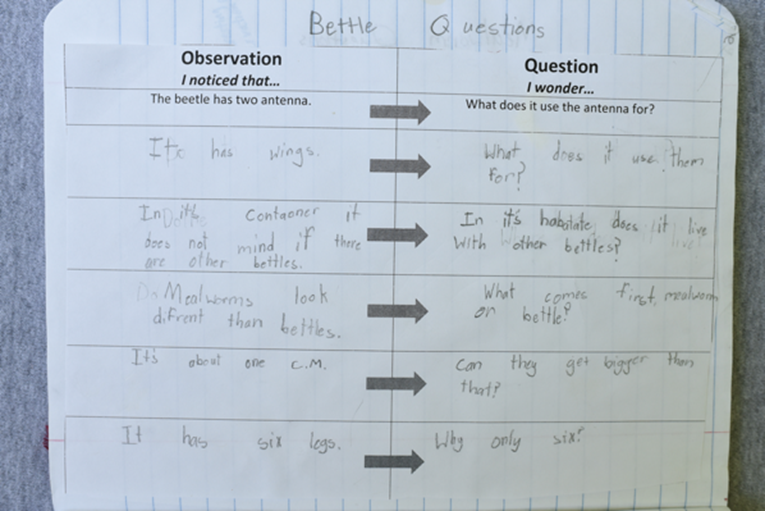

Write questions

Next, challenge students to select a few of their observations and write questions based on them. For example, if a student observes that a rock has shiny flecks in it, they might ask the question “What makes the rock sparkly?” To help ensure student success, you might model this process for students through a think-aloud and provide this graphic organizer for student use. You can also provide question sentence starters to help students think of questions to ask besides Why…?. As students become comfortable with the process, encourage them to increase the diversity of their questions.

Use the questions

Student-generated questions can provide the basis for further research and investigation in either science or English Language Arts time. You could also use the questions your students generate as the start of the Question Formulation Technique (QFT) protocol, in which students classify questions as open or closed and practice turning them from one form to the other. It is important to not skip this step, as students will likely become frustrated by generating questions and then not being able to answer them.

Curiosity is like a muscle—the more students practice wondering, the better they will be. And once your students are proficient questioners, the sky is truly the limit for their learning!

Featured image credit: “Questions” by Oberazzi is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Jessica Fries-Gaither is an award-winning author of books for children and teachers. Her writing introduces readers to the wonder of the natural world and the work of scientists, past and present. She is finishing a year as an Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellow at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. and is returning to Columbus School for Girls in Columbus, OH, where she teaches Lower School (grades 1-5) Science. Learn more at her website, www.jessicafriesgaither.com and follow her on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/jfriesgaither, on Instagram at @JessicaFGWrites, and on Blue Sky at @jessicafgwrites.bsky.social.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.